Signs and Summits

I. The Detachment of Signs

At Refugio Paine Grande, over Cup Noodles, a young Australian hiker asked if I could explain the connection between Patagonia the place, the brand, and the tradfi vest.

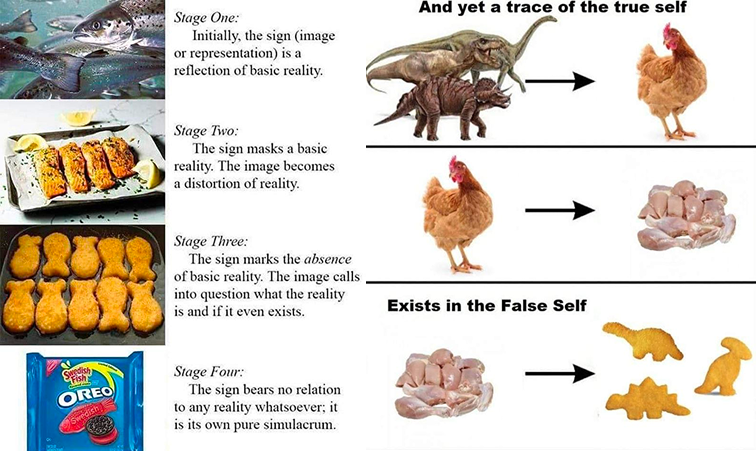

The question revealed how far symbols drift from their origins. The fleece vest, once made for climbers and backpackers, became a post-2008 corporate uniform—what historian Margaret O’Mara called “the right sweet spot between East Coast money and West Coast casual.” It was memed into ubiquity through the Midtown Uniform Instagram account, its sign value detaching from any environmental referent.

Patagonia the company tried to reclaim that reference—restricting corporate sales, banning logo embroidery, and even revising its mission statement: We’re in business to save our home planet. Yet the vest persists in Midtown. Kill one market, another appears. Baudrillard would call this hyperreality: a symbol consumed entirely for its sign value, circulating as status rather than substance.

II. Just Doing Things

Five days trekking through Patagonia was simple but not easy. The hardest part was deciding to go; the second hardest was getting up each morning—regardless of weather, fatigue, or mood—to keep walking.

What does it mean to “just do” something in a culture obsessed with metrics, outputs, and documentation? To walk without tracking steps, to move through a landscape without extracting value from it? There’s a heresy in that.

The objectives were starkly simple: wake up, pack, walk. And in that simplicity, spaciousness. An absence of digital fragmentation. Muscles adjusting to terrain, lungs to elevation, feet to rock and soil. A wisdom accumulated through the body, not the feed.

Rebecca Solnit once wrote: “The rhythm of walking generates a kind of rhythm of thinking.” Patagonia (the place) reminded me of that truth.

III. Knowledge Communities and Non-Extractive Systems

My ability to trek Patagonia at all was scaffolded by a web of collective knowledge: ultralight hiking forums, blogs, packing list tools, and trail reports. These weren’t corporate platforms designed to monetize attention; they were archives of obsession, maintained by enthusiasts who shared what worked, what broke, and what weighed too much.

I’d seen this dynamic before in music technology. Modular synthesizer communities built tools like ModularGrid to virtually plan systems before ever buying hardware. What unites them is an ethic: knowledge circulated to empower autonomy, not capture it. Each gram logged in a spreadsheet, each module diagrammed, each trail report uploaded—small acts of generosity that compound into distributed expertise. These systems don’t extract value from their participants. They enhance it.

Patagonia itself once played this role: its 1980s catalogs doubled as field manuals, teaching layering systems and wilderness philosophy alongside selling gear. They seeded a culture as much as a product line.

IV. Born of Obsession, Claimed by the Planet

The brand’s own history begins not in a boardroom but in direct experience. In 1968, Yvon Chouinard and friends spent six months climbing Mount Fitz Roy in the Southern Patagonian Ice Field—the very terrain that later inspired Patagonia’s jagged skyline logo. The company grew out of this obsession with climbing and craft: first forged pitons in a Ventura tin shed, then outdoor apparel designed from lived necessity.

By the 1980s Patagonia was investing heavily in material research, pioneering fabrics like Synchilla and Capilene, and using its catalogs as cultural texts that taught outdoor ethics as much as they sold gear. Over time, the company aligned more explicitly with environmental stewardship: pledging 1% of sales to conservation, certifying as a B Corp, and eventually becoming California’s first legal benefit corporation.

In 2022, the Chouinard family took its most radical step: transferring ownership of Patagonia to a trust and nonprofit, effectively giving the company away to fight climate change. As Chouinard declared, “Earth is now our only shareholder.” In a landscape where brands often detach entirely from their referents, Patagonia tried to re-anchor itself in embodied origins and ecological responsibility.

V. Artifacts of Obsession

Coming back from my trek, I carried the same energy. It condensed into a weekend coding sprint: an ultralight hiking index built with Vercel’s v0, Claude, and Deep Seek.

The index was an artifact of obsession: something made because the experience demanded expression, and because it might help someone else. In Ivan Illich’s terms, a convivial tool—technology that strengthens autonomy instead of breeding dependence.

VI. Recursive Systems

Patagonia has institutionalized a similar impulse through Tin Shed Ventures, its venture arm named after the shed where Chouinard forged climbing gear. The fund backs startups addressing climate crises and building circular systems like Worn Wear.

Where the vest became a detached simulacrum, Tin Shed tries to ground the brand again in material reality: financing companies that tie environmental stewardship to tangible systems. It’s another artifact of obsession—scaled up to the level of capital.

Patagonia’s history itself is recursive: Chouinard’s mountain experiences birthed gear, which enabled further experiences, which inspired new gear, which evolved into a company now reinvesting in environmental preservation.

My loop was smaller but parallel: a trek led to an index, which may support future treks, which might in turn inspire new tools. Both are counterflows against linear extraction, opting for recursion and circularity.

VII. Grounding

The Australian hiker’s question lingers: what connects Patagonia the place, the brand, and the vest?

The truth is, maybe nothing does anymore. The vest has floated free as a symbol of finance and casual power, while the brand wrestles to reclaim its ecological roots. The place itself remains indifferent. Vast, glacial, and real.

But the act of doing—walking, building, creating—offers a way back. Direct experience doesn’t stitch these three together neatly; it refuses neatness. What it does is reopen a channel between representation and reality. Trekking, coding an index, or repairing a jacket in Worn Wear all point toward the same possibility: that meaning doesn’t come from symbols alone, but from the recursive loop between embodied experience and the artifacts it inspires.

In a world where signs float increasingly free, that loop is the counterflow.